The Curious Case of the Jaeger-LeCoultre Lamp Post Clock

By Troy McHenry

As someone who has been captivated by Jaeger-LeCoultre wristwatches for a long time (check out My Watch Story on HODINKEE if you need proof), I should have known that it was only a matter of time before their long history and varied production of clocks would eventually find their way to me. With the rising costs of wristwatches, whether new, contemporary or vintage, I’ve found the world of smaller desk and table clocks a fun diversion to dip my toe in between watch purchases.

Of course when you think Jaeger-LeCoultre and clocks, the first thing that comes to mind is their famous Atmos carriage or mantle style clocks. The idea of a “perpetual” clock that is wound by miniscule changes in temperature is pretty hard to pass up. I ended up buying an Atmos clock a few years ago at an auction near my house. It had a plaque for a 40 years of service anniversary for an employee at AMC (not the meme stock, but American Motor Company, maker of such timeless models like the Pacer and Gremlin). Unfortunately, the bellows in my clock, the small bladder that expands and contracts with temperature changes, has a leak, so it’s never kept accurate time, except twice a day, and while there are several clockmakers that specialize in restoring Atmos clocks to their former glory, the relatively high cost and limited warranty on the aftermarket parts hasn’t exactly made me want to greenlight the repair just yet.

Slightly discouraged, I settled onto the idea of getting a smaller, more traditional mechanical powered table clock. Many great ones by Jaeger-LeCoultre feature their renowned eight-day movements requiring it to be wound only once a week. After looking at various tattered leather travel clocks and floating mystery dial and in-line movement clocks, I discovered the lamp post series of clocks by Jaeger-LeCoultre. They’re not hard to miss, fairly ubiquitous on eBay and they also pop-up from time to time in the catalogs of the larger horological auction houses like Antiquorum. Originally marketed as the “Gaslight Clock”, what I’ve come to realize is they are singularly unique to the maison and among small clocks. They have also been very illustrative of Jaeger-LeCoultre’s history during the 1960’s and as I later discovered, hold a wealth of mysteries and surprises unto themselves.

Rue de la Paix

What stood out to me when I first encountered one of these clocks was the little blue street sign attached. I’d surmise a full 95%+ of the clocks feature the Parisian street, “Rue de la Paix”. A direct translation would be, “Street of Peace” or “Peace Street”. I first thought the street sign was perhaps a subtle, not so subtle, reminder of Jaeger-LeCoultre’s location in the city. Last time I was in Paris, I remember walking the streets with my wife and visiting the Jaeger-LeCoultre boutique,... at 7 Place Vendôme.

So why Rue de la Paix? Did Jaeger-LeCoultre have a boutique there at one point? The street Rue de la Paix does turn into Place Vendôme after all. From all my research the answer is no, the street had no specific significance for Jaeger-LeCoultre, but instead, the clocks with the Rue de la Paix street sign were really just thought of as quintessential Paris, much like having a clock with Rodeo Drive could spark memories of Beverly Hills. Rue de la Paix was the original street in Paris for couture fashion and jewelry. Interestingly, the street is also known as Cartier’s “ancestral home” at 13 Rue de la Paix; they've been there since 1899. Makes me chuckle that it could be thought of as free advertising for a competitor, but now both are part of the Richemont group. The shopping advertisement below attests to the street’s significance. For Paris tourists, a reminder of the famous street and shopping district seems a relevant souvenir. It’s important to also note, these were made in a time before Jaeger-LeCoultre had boutiques, so most purchases would have been through an authorized retailer. So, the question presented itself, “Did a particular JLC retailer on Rue de la Paix have these clocks commissioned?” Again, all signs point to no.

Prototype JLC Circa 1960. Image credit: Jaeger-LeCoultre

Two American market Rue De La Paix LeCoultre lamp clocks. Image courtesy of Jaeger-LeCoultre

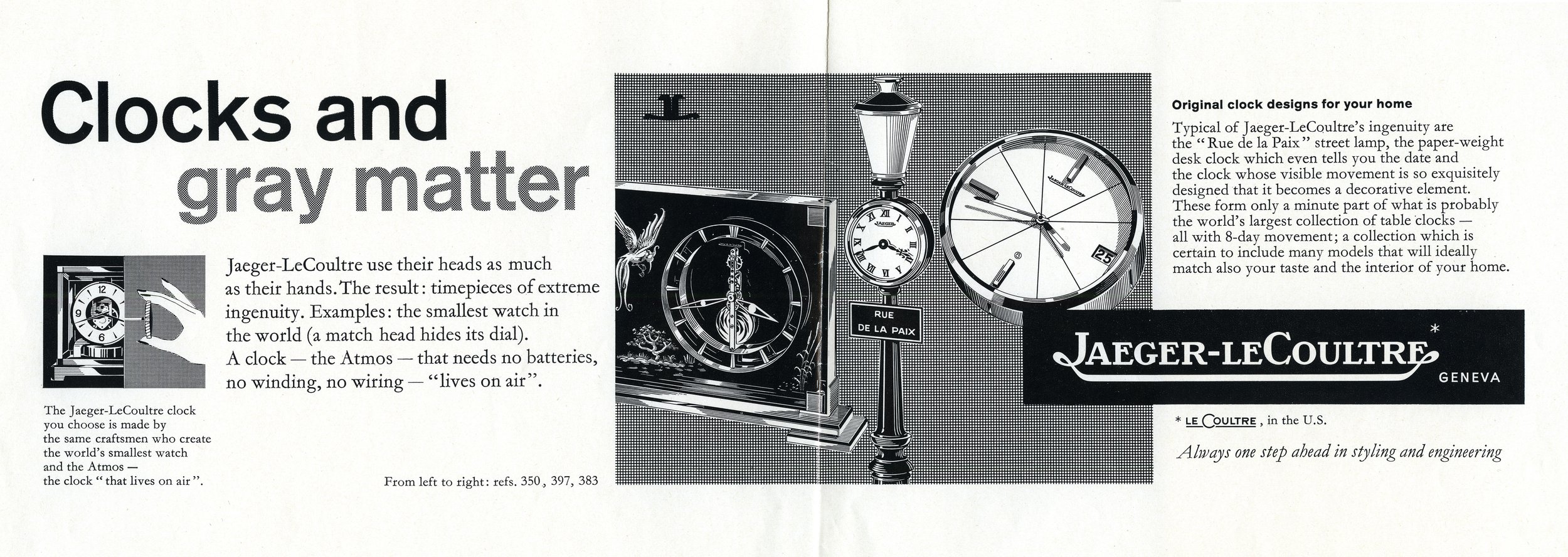

Looking at advertisements during the time period for these clocks confirms the same sentiment that the clock’s street plaque was just to invoke general Paris emotions. I love the ad copy, “a touch of Paris” and “designed with imagination and taste”. I couldn’t agree more.

When you go through the past 20 years of auction results, the other recurring street names start to become clear and can really be grouped into two categories, Paris-based streets and other streets across the globe. It’s important to note all these other names came later, based upon and building on the success of the original gaslight clocks that all featured exclusively Rue de la Paix at the beginning. Notable Paris street names that made later appearances on these clocks include: Avenue Victor Hugo, Rue Jeanne D’Arc, Place de L’Opera, Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, Place de la Concorde, and Rue Royale. All these later Parisian street names are exceedingly rare and similar to the more common Rue de la Paix are general street names, i.e. no specific street or house number given, which makes sense since they are meant to be street signs. However, one notable mysterious recurring exception occurs, that includes a specific street number, which is: 208 Avenue de Versailles. I have spent more time than I care to admit trying to figure out why this particular address was produced. Unfortunately, today it’s a modern building and parking deck. Going through old French business listings, the address was once a girls’ school, and later it appears to have been the location of a small shopping center. My best guess is a jeweler and JLC retailer that was located at this address had them commissioned.

A directory listing from the same time period that the clocks were made containing the aforementioned address

The non-Paris based street names are quite varied, everything from Wall Street and Bourbon St in the United States to supposedly ones for Portobello Road in London and Hamburg’s Reeperbahn also exist. I even found an example where the street sign was replaced with the name of an employee for use as an award; congrats to Edward Kasouf, the Hiram Walker Line Builders Award Winner of 1964 (boss award by the way Hiram Walker & Sons Distillery). The only other non-street reference I’ve found is one with a Coca-Cola logo. I have no idea of its authenticity or if it was done as a later modification.

Other Varieties

Beyond the assortment of street names, there’s incredible diversity in a number of factors when it comes to these clocks. Take for instance the color of the actual lamp post, most commonly found is black lacquer, but they can also be found in green lacquer and polished gold plated. The black and green ones offer gilt trim/highlights while the gold ones are trimmed in black. I’ve heard rumors of a “wine red” lamp post clock as well, but haven’t been able to verify its existence. Looking at an early advertisement, only black and green are mentioned, the polished gilt/gold came later during the overall production run.

Beyond the three available colors of the actual lamp post, the lamp shade itself, always made of plastic, can be found in three different colors. On the black and green lamp posts it’s always an opaque white or cream color. However, on the later gold ones a clear lamp shade was introduced along with the opaque ones. Personally, I prefer the opaque ones since it keeps the fantasy alive, while the transparent shade unveils how these clocks are constructed, which we’ll get to later.

When I first started learning about these clocks my first questions were actually when were they made and how many? In discussing this with Laurent Kervyn de Meerendré, Senior Product & Heritage Manager at Jaeger-LeCoultre and his team, the exact number made is unfortunately lost to history. However, looking over past catalogs does help shed light on when these were produced. The first occurrence is in a Jaeger catalog dated 1959 and is mentioned as a “Rue de la Paix” alarm clock. That same year, it also debuted in a Jaeger-LeCoultre catalog. There it shares the same Jaeger-signed dial, however, it is referred to as a “Bec de Gaz” or gas lamp clock. These clocks appear in catalogs continuously from 1959 till 1970. There is no mention of them from 1971 through 1973. They make one last appearance in the 1974 catalogs before disappearing for good.

This time period is interesting for any Jaeger-LeCoultre collector (clocks or watches) because the Maison were using three different names depending on the market and time period, which means there is diversity in the dials as well. In the United States they were branded as LeCoultre, while in Europe and the rest of the world as Jaeger or Jaeger-LeCoultre. If that’s not enough, one recently appeared on eBay with a dial marked for the German jeweler, Gübelin.

What all these dials do have in common is they are all printed with roman numerals in black and the dial is cream in color. That being said, there’s one singular example I’ve found of a different dial color, which was sold by Christie’s back in 2008, which features a red lacquer dial marked Jaeger-LeCoultre with white printed roman numerals and apparently lume plots given the dots and the “T Swiss T” markings at the bottom of the dial for tritium. This clock is also the title holder for the most expensive lamp post clock since it sold for approximately $8,800, nearly 3x its high estimate!

Image credit: Christie’s

Image credit: Christie’s

Movements

Besides differences in colors and appearance of these clocks, movement-wise there were several different ones offered throughout the years. Everything from time-only to 12-hour alarm movements to 24-hour alarm movements with a day/night indicator (these are typically marked “Recital” on the dial). Most have an 8 in a circle near 6 o’clock, indicating that the movement has an 8-day power reserve.

If that wasn’t hard enough to keep track of, there were several different iterations of these movements used throughout the production run. Let’s start with the most basic model, the manual-wind, time only. These clocks tend to be designated as model/ref. 397 or later 457. The movement typically found in these is the caliber 245. Famously, while the dial is mentioning a power reserve of 8 days, these movements typically can go up to 10 days between windings. The 12-hour alarm models are listed as model/ref. 45, the alarm or “réveil” movement used is the caliber 219. These are easy to spot since the alarm is set and shown with a stick hand.

From left to right: time-only movement, time and 12-hour alarm movement (note the stick hand for the alarm)

From left to right: 24-hour alarm movement with alarm indicator at 12 o’clock, 24-hour alarm movement with alarm indicator at 6 o’clock

Lastly, the more modern and useful 24-hour alarm or “recital” models are listed as model/ref 107. The caliber used in these are all different iterations of the caliber 240. When looking at the movement, it’s not uncommon to see the movement listed as 240/1, 240/2, and 240/3 denoting the iterations. Instead of a hand for showing the time set for the alarm, it’s a 24-hour wheel that is turned from the back and is shown to the user by means of a cut out on the dial, either at 12 o’clock (originally) and later at 6 o’clock. The clock even has an am/pm indicator as shown as a little disc behind the hands that rotates. Unlike JLC Memovox wristwatches, when the alarm is wound, it does not use up all the power and sound once. Instead, a full wind of the alarm mainspring is good for 14 daily 10-second alarms! Below are a few more of the highlights of the 240 movement.

Highlights of the 24-hour alarm caliber 240

Ownership

Seeing one of these in person is quite a treat since they are almost a foot tall and when you pick one up, they are impossibly heavier than you’d imagine (the same thing I’ve heard told to people who pick up an Academy Award for the first time). The base and post are all solid metal. Winding the clocks is straightforward with using a flange that folds out of the way when not needed, but can be flipped out to help turn and wind the mainspring. The movements being more clock than watch, are fairly robust and problem free.

The main parts of the lamp post clock in their correct sequence. (1” cube in top-right to show scale)

However, there is a fundamental weakness in the design. The way the clock is designed, there are three main parts of the clock, 1) the case for the movement which also contains the crystal and it has one threaded hole on the top and bottom of the clock case, 2) the top elements, including the lamp, and finial elements are slid over a short metal rod and the very top of the clock screws in to keep everything nice and tidy (above is a picture of the parts of part 2 deconstructed), and 3) the bottom portion of the lamp post clock which is the heavy base and main post/trunk of the clock. It connects to the bottom of the clock case, just above the sign with a small threaded screw. The reason for this chosen design is it would be impossible to have a long metal rod run from the top to the bottom of the clock since the movement would be in the way. The problem that exists then is, because of the considerable weight of the base and the torque that is required to wind the clock, if the owner holds it from the base and then winds the clock, which feels natural to do, puts too much lateral force on the small screw that holds the top two parts of the clock to the base. It’s not uncommon for the screw to break or become unscrewed at the base of the clock’s movement, making the top have a rakish tilt. To fix this, the back of the movement must be removed, then two retainer clips unscrewed, the movement removed and then the screw can be tightened, not an easy job. When assessing to purchase one of these clocks, ask if the top wobbles at all. If it does you may be looking at a costly repair.

An example where the middle screw has either worked itself loose or has been bent from winding the clock.

Examples where the parts that make up the “lamp” portion of the clock are out of sequence.

Since the design elements that thread onto the rod to make up the top part of the clock (the lamp portion), are all free-floating, the top can be unscrewed and the pieces mixed up from their correct order. The good news is this is an easy fix, just unscrew the top, remove the pieces and rearrange them into their correct order and slide them back onto the clock. In turn, this is sometimes a good way to get a lamp at a discount since through the years it seems these pieces can get mixed up which may scare other potential buyers away. It also makes for a fun online game to see how many for sale listings can you spot where the pieces of the lamp are in wrong sequence, such as these poor beauties:

Concerning market prices, these clocks were originally retailed for $29.95. Taking a typical year in the middle of their production cycle, say 1965, and accounting for inflation, the price today would be: $281.70. This means while not inexpensive, they weren’t super expensive either. In turn, these lamp post clocks can show up at any yard sale or small auction and routinely show up on eBay, where at any given time there may be 3-6 for sale.

I documented all the sales of these lamp post clocks for the past 12 years across all auction websites (Christie’s, Sotheby’s, Bonhams, Antiquorum, Live Auctioneers, eBay, etc) including name on dial, post color, movement type and source where it was sold. Adjusting for inflation, I wanted to test and see are these clocks going up or down in value and which attributes should a collector consider when making a purchase. Above you can see some of the completed lots plotted by price over time and in this case, taking into account if the name on the dial was marked “Jaeger” or “LeCoultre”. Jaeger-marked clocks have been holding their value slightly better than LeCoultre-marked clocks and appear to command a higher value, but some of that is driven by outlier sales. This is probably more of a function of the LeCoultre ones overwhelmingly being sold at smaller US-based auctions and through eBay. Looking at the entire dataset again, you can derive the following data points:

By Movement

Avg price for time-only: $726

Avg price for 24-hr alarm: $892

Avg price for 12-hr alarm: not enough data points

By Lamp Color

Avg price for black: $724

Avg price for gilt: $703

Avg price for green: $1,508

By Auction Source

Auction house: $928

eBay: $415 (sold listings only)

In turn, if you’re looking for a deal, leverage those saved searches on eBay.

In Closing

While I consider myself first and foremost a watch collector, it’s been fun dipping my toe into “clock waters” and in the process gaining a far deeper appreciation for one of my favorite brands, Jaeger-LeCoultre. While I don’t think you’re going to see me lecturing at a NAWCC symposium anytime soon on JLC clocks, I have grown a deeper appreciation for our clock collecting brethren. I can’t help but think, with Jaeger-LeCoultre’s flagship boutique firmly established in Paris, perhaps the time is right to re-issue a version of the lamp post clock but with the street sign proudly stating their current address, No. 7, Place Vendôme. Much like the reason for these clocks’ existence in the first place, to rekindle at a glance that love affair with Paris, one can dream, oui?

Further Lamp Post Clock Diversions

While the world of Jaeger-LeCoultre lamp post clocks is incredibly diverse for the limited time they were manufactured, the rabbit hole can go deeper. For instance, there are some really fascinating prototypes (did they ever make it to production?) that are worth additional scholarship as well as other brands that introduced similar lamp-post style clocks (copy cats?).

The closest thing to an actual Jaeger-LeCoultre lamp post clock was this clock near the (now closed) Jaeger-LeCoultre boutique in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Photo from Horomundi.com

Other mid-century lamp post clocks. Note, the two on the right are from Jaeger-LeCoultre. Two right pictures courtesy of Jaeger-LeCoultre and Blomman.

Marketing Material

The predecessor lamp clock from the 1930s.

Jaeger catalog for the French market featuring the reference 72 and reference 45 circa 1959. Image courtesy of Jaeger-LeCoultre.

Catalog featuring the reference 397 and reference 399 circa 1960. Image courtesy of Jaeger-LeCoultre.

Jaeger Rue de la Paix reference 397 and reference 427 circa 1962. Image credit: Jaeger-LeCoultre

Jaeger-LeCoultre clocks reference 354 and Rue de la Paix reference 397 circa 1961. Image credit: Jaeger-LeCoultre

Jaeger-LeCoultre clocks reference 427 and Rue de la Paix reference 397 circa 1963. Image credit: Jaeger-LeCoultre

JLC reference 514 and Rue de la Paix reference 457 circa 1969. Image courtesy of Jaeger-LeCoultre

Jaeger-LeCoultre brochure, courtesy of Jaeger-LeCoultre.

Ed Urs Haenggi advertisement featuring Jaeger-LeCoultre clocks.

"Pendulette Les réveils ciselés". Ornately decorated Jaeger clocks from the 1960s adjacent to an advertisement featuring Memovox models, the Armor and the Lamp Post clock. Image courtesy of Jaeger-LeCoultre.

8 Day JLC Clocks featuring the calibre 240 adjacent to an advertisement featuring Memovox models, the Armor and the Lamp Post clock. Image courtesy of Jaeger-LeCoultre.

Jaeger-LeCoultre reference 439 clock adjacent to an advertisement featuring Memovox models, the Armor and the Lamp Post clock. Image courtesy of Jaeger-LeCoultre.

Several Jaeger clocks for the French market. Image credit: Europa Star (LATIN AMERICA | 1964 | ISSUE #84).

LeCoultre Gaslight Clock. Image credit: Hartford Courant Hartford Connecticut (May 14, 1967)

Image credit: News Fort Lauderdale, Florida (Dec. 18, 1966).

Jaeger-LeCoultre advertisement for the Japanese market circa 1968. Image credit hifi-archiv.info.

Jaeger-LeCoultre advertisement for the Japanese market circa 1969. Image credit hifi-archiv.info.

Acknowledgements

While we tend to think everything exists online, for the materials and research required for this article, that was decidedly not the case. I would like to thank Tony Traina for giving me the initial encouragement when I shared my idea of telling the story of these unusual clocks, the product marketing managers and heritage directors at Jaeger-LeCoultre for their enthusiasm and invaluable help including Matthieu Sauret, Laurent Kervyn de Meerendré, and Ilham Moutaa-Lecorche. Watch collector and fellow Jaeger-LeCoultre enthusiast, Blomman, from the Blomman Watch Report, who blazed a trail in the initial online documentation of these endearing clocks. Thanks also goes to Serge Maillard at Europa Star and Liam Bolland at Fellows for opening up their archives for me to explore. Lastly, to Charlie Dunne, for his mutual passion for all things JLC, graciously supporting this effort, and offering his platform, passion, and expertise to help tell this story.

You can find Troy on Instagram @TheGrumpyCollector and his podcast, The Grumpy Collector, on all major streaming services. Troy is a co-leader of RedBar, Raleigh Chapter, and one of the newest members of HSNY and NAWCC. He resides in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.